TORSTEN ANDERSSON: "SKUGGAN" ["the shadow"]

TORSTEN ANDERSSON

"SKUGGAN" ["THE SHADOW"]

25.04.-24.05.2025 / PREVIEW: Friday 25.04.2025 / 19:00-21:00

-----

"Their farewell was memorable. Neary came out of one of his dead sleeps and said:

"Murphy, all life is figure and ground."

"But a wandering to find home," said Murphy."

- Samuel Beckett, "Murphy", Routledge, London, 1938

If you put a painting on fire, will the smoke that rises from it contain all the colours that it was made from? Or does it merely end up desaturated and reduced to some shade of grey? The same colour that we associate with age, dullness and tiredness. The same colour that we have assigned to the concept of modesty. The same sort of modesty - the unassuming belief in one's own abilities - that had Torsten Andersson doubting his paintings once they were completed. That had him thinking that they were simply not good enough, as he was dragging the eight large paintings that had just returned from the Louisiana Museum into the fields. There, at a safe distance from his house and his studio, he took out some matches, lit up a few rags that were soaked in turpentine and oil paint, and tossed them onto the pile of paintings.

Hours later, a simple circle of soot had taken its place; a charred grey punctum interrupting the flowing and pale yellow fields of Benarp. It was a period, marking the end of a period: the end of the painstaking process that had gone into making these paintings. What had started with a drawing, then yet another drawing, then tens and hundreds of drawings of the same composition that had Andersson obsessively striving to figure out his motif, repeat it, reconfigure it, subject it to a differing of inflections - first in pencil on paper, and then in an equally absurd amount of attempts in oil on canvas - had yet again failed to convince him. Torsten Andersson was not easily impressed: "Quality is easy when you copy, but how the hell do you make something that is better than good?" The question had so brutally confronted him as a young artist back in 1966. Not being able to provide a persuasive answer, it had forced him to abandon a promising career backed by Stockholm's leading gallery, to leave his position as a professor at the city's art academy, and to move back to his native Benarp, in the south of Sweden. For six years, between 1966 and 1972, he did not make a single artwork.

"Such a person does not exist!" 20 years later, a young curator of Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Lars Nittve, is trying to find his way to the studio of Torsten Andersson. He seems to have lost his turn. He is unsure of the address. And when asking a local farmer for directions, he is told that there is no such painter living in these parts of Skåne. The twenty years spent away from the art world had made Torsten Andersson invisible to critics, curators, collectors and neighbours alike. However, what Nittve was about to learn, was that Andersson's isolation had permitted for an entirely unique body of works to take form. Since initially staying away from his studio, Andersson had completely committed himself to an inspection of what painting could be, what painting needed to be, in order to be "better than good". The manic manner with which works came into being, and just as frequently came to an end, was in fact a two decade long struggle for Andersson to figure out a language of his own. The punctum was just as much of a colon: only by burning and abandoning previous attempts, could he make room for new attempts.

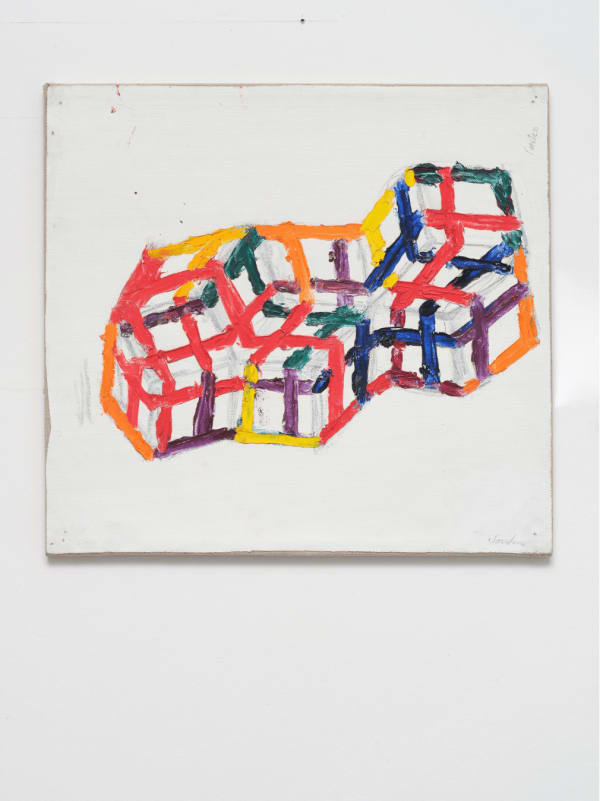

What had taken shape over these years was a peculiar group of works, which can be best described as realist paintings of abstract sculptures. It was as if he had focused all of his energy in the studio to suspend the swinging of the art historical pendulum; to challenge the notion that historical progress is made through a continuous battle between seeming opposites. And rather than succumbing to making provincial variations within the vernacular of changing international styles - isms, that were intermittently proposing realism, symbolism, illusionism, formalism, or, as it happened to be when Andersson quit painting in 1966, minimalism, which pursued the pure objecthood of monochrome painting - he strived to find a third road. "The Benarp Road [Benarpsvägen]", as Nittve titled his catalogue essay for the Moderna Museet retrospective in 1986, which had taken Andersson to his childhood home. Only here could he gain the courage and capability to distance himself from the expectations, his education - rooted in a Modernist tradition - and the perception of representation as a problem. Here, in the Swedish countryside, he started pulling on a different set of resources, such as heathenish emblems and gothic church sculptures, the myths and memories of rural Skåne, and the sense of belonging to this landscape that had so masterfully been depicted by fellow Skåne painter Carl Fredrik Hill (1849-1911). Andersson was seeking out a painting that located itself at the intersection of nature and culture, and there he found archetypes that could be turned into new prototypes.

More than any other motif, the monuments of modernism recurred as the focal point of his paintings. With great precision and poetic license, he rendered these triumphant sculptural forms out of balance, deprived them of their sense of authority, and consistently captured them in a state of unease or embarrassment. Such is evident in "Kansersjuk skulptur [Cancer-Ridden Sculpture]" (1992-1994). The title that is prominently placed on the canvas, is insisting on being noticed first. Only when that has set the mood, can your eyes wander to the wavy black figure that positions itself at the centre. The paint has been coarsely, yet confidently laid out with a palette knife. Several furrows are allowing for hues of pink to appear from the underpainting - suggesting a second layer of skin. "An important painting is a painting in human shape. An important painting is a human being in painting shape, Andersson was quoted saying, and has here forced the corporal onto the otherwise austere and abstracted surface - maybe less so in the form of a body and more in the movement of a body. Hunched over and exhausted, it is as if a Brancusi sculpture just emerged from the depths of a coal mine, coughing violently and brushing off layers of dust. The title does hardly anything to diminish that feeling: it is a public sculpture that has a deeply private problem.

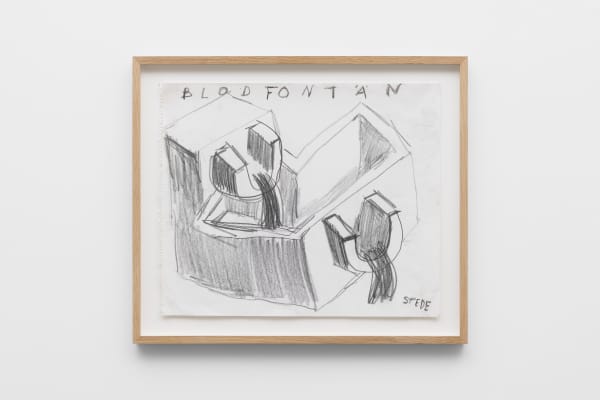

A few steps away from the painting hangs a drawing of a spiralling structure. Executed in graphite on paper, it is marked by the same haste and harshness. Even more so, the two works bear resemblance in terms of the movement of the painting doubling as a bodily movement - the biomechanics, so to speak, that sets the composition in motion. The undulating form at the centre of the drawing has the words scribbled next to it: "Jomfru Marias Navelsträng ["The Virgin Mary's Umbilical Cord"]." Andersson himself employed the term "biological architecture" for a similar suite of his paintings from the 1980s, which rendered organically shaped building elements in various landscapes. "Motherforms

Planted In the Fields" ["Moderformer planterade i markerna"], was the title he gave them, and even equipped some of these edifices of monumental scale with teats or the curves of a pregnant woman's stomach. The words and form chosen are brimming with insistence and impossible ambition: Andersson is laying bare a struggle to find the very building blocks - the Urgestalts - of painting, language and life itself. Not only taking the umbilical cord, that supports every life coming into being, but monumentalising this particular one of the Virgin Mary - which Andersson allows to float graciously between the actual and mythical - that is the very connection between human beings and a higher being. And in doing so, the drawing points towards an inherent paradox in the works of Torsten Andersson: the urge to understand something by repeatedly drawing or painting it, while what is being attempted to to be understood is something that does not exist. Or something that could not be proven to have ever existed. Or something that cannot be understood, even if it did exist. Yet, one has to try! And possibly - almost certainly - try again! He claimed that he did so many repetitions because it took some time for the paint to dry and for the painting to solidify and present itself. Only then could he see whether it was any good. Most often he was not convinced and carried it out into the fields. He was incapable of surrounding himself with mistakes and he could not stand painting on top of old oil paint. Too many colours on top of each other just result in an ambiguous grey.

Next year will mark the 100 year anniversary for Torsten Andersson's birth. Born in Östra Sallerup, in the Skåne region of Southern Sweden in 1926, he graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 1950. After early success as a young painter - which included several exhibitions with Galerie Blanche as well as inclusion of the São Paolo Biennial in 1959 - he abandoned his career and life in Stockholm, and returned to his childhood home in Benarp in 1966. After a six years pause from making artworks, Andersson returned to his practice and was in 1986 subject of a major retrospective exhibition at Moderna Museet in Stockholm as well as Malmö Konsthall in Malmö in 1987. Other exhibitions include "Sextant. Six artistes suédois contemporains" at Centre Pompidou, Paris (1981); "The Louisiana Exhibition", Louisiana, Humlebæk (1997); "Zeitwenden", Kunstmuseum Bonn, Bonn (1999); as well as "Carnegie Art Award", which he won in 2007 - two years before his death in 2009 - with a touring exhibition that included such venues as Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, Helsinki; Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Høvikodden; and The Royal Academy of Art, London. Later this year, Andersson is subject to a solo exhibition at Dalslands Konstmuseum in Upperud, Sweden.

This exhibition is developed in collaboration with Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm, and the Torsten Andersson Foundation, Stockholm.

For further information please visit our webpage: www.standardoslo.no or contact Eivind Furnesvik at eivind@standardoslo.no or +47 917 07 429 / +47 22 60 13 10. STANDARD (OSLO) is open Wednesday-Friday: 12.00-17.00/ Saturday: 12.00-16.00. Sunday and Monday: Closed. Tuesday: Open by appointment.

-----